Explain Mindfulness to children

Explaining mindfulness to children and how brain works can seem a daunting task. Infographic below will make it easier.

I explain this so often to adults so when I came across this article on how to explain it to children I thought I must share. The original post can be found here.

Explaining how mindfulness and the brain works can seem a daunting task, yet it can be one of the best ways to show how mindfulness works for us and how it helps our brain to function properly. If you are in a hurry, you can scroll down to the big infographic. So what is mindfulness? Mindfulness occurs when we pay attention to what is happening in the here and now. We observe our emotions, our thoughts, our surroundings, in an even-minded, nonjudgmental way.

We apply this same focus of attention to situations both good and bad. This is being mindful. Learning to be mindful of what’s happening in the moment helps children make sound decisions rather than be ruled by their emotions. Negative emotions can be tough for anyone to deal with. Fear and anger can hit us unexpectedly and when we do not have a prior plan for dealing with these feelings, we can be thrown off balance and react badly.

When a 4th grader reports that she felt she “was going to die” from test anxiety, she’s telling the truth. The responses of her autonomic nervous system are the same whether she’s taking a math test or sensing actual physical danger. – Mindful Schools

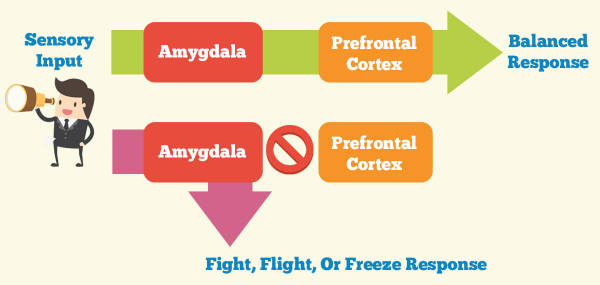

Here’s what science has to say about it. An impulsive reaction, triggered by emotions like fear or anger, rises up from the amygdala and hippocampus—the most ancient parts of our brain. These parts evolved to respond with defensive action to threatening situations. If we can delay this reactivity, the newer pre-frontal cortex of the brain can respond from a place of reflection and thoughtfulness. The PFC (pre-frontal cortex) is associated with maturity, including regulating emotions and behaviors and making wise decisions. Mindfulness practice, as you may have guessed, diminishes the reactivity from the amygdala and strengthens the pre-frontal cortex.1

The growing brain and mindfulness

Author and anger management clinic director Dr. Ronald Potter-Efron explains that the newest parts of our brain—and the last parts to develop as we grow—likely evolved in response to an increased propensity to live in groups. “As we have learned to live together collectively, the human brain has been spurred to grow accordingly.”2 A lot of growth is taking place in the adolescent brain, and this growth is happening at the same time that the brain is reorganizing itself.

“Part of this reorganization process,” says neurobiologist Dr. Arlene Montgomery, “includes the pruning of disused neural connections. This growth and pruning are affected by environmental experiences and reshape the adolescent brain.”3 This is one of the reasons mindfulness in childhood and adolescence can be so effective: the pathways that foster empathy and impulse control are being used and strengthened, which will serve the child throughout his or her life.

Mindfulness and the brain

The amygdala determines emotional responses by classifying sensory input as either pleasurable or threatening. Input seen as threatening is blocked by the amygdala, prompting an immediate reflexive reaction: fight, flight, or freeze.4 The amygadala does not see a difference between perceived threats and actual dangers. It often triggers “false alarms” and potentially problematic reactive behavior. We sometimes freeze in stressful situations, like public speaking or when taking a test.

Though neither of these activities are life-threatening, we disconnect from rational thinking and become impulsive and reactive. Even if we have conflict resolution skills stored in memory, we might not be able to access them due to the stress response, as the amygdala hinders access to memory recall and storage. When we have the time to consciously process sensory input, we allow the prefrontal cortex to analyze the information. Instead of an immediate, impulsive reaction, we get to choose the best response instead.

Practicing mindfulness calms the amygdala and reconnects us to our calm, clear prefrontal cortex, so that we can make thoughtful choices for how to respond. Mindfulness helps us regain access to our executive functions: the intention to pay attention, emotional regulation, body regulation, empathy, self-calm, and communications skills—even when under stress arousal. Mindful thinking happens when the prefrontal cortex can process the information.

Following your breath or counting to ten when you’re angry or sad gives time for the amygdala to allow the information to flow to the prefrontal cortex to be properly analyzed. Mindful Schools reports that research has found improvements in anxiety, cognitive functioning and self regulation among children trained in mindfulness, suggesting that the corresponding parts of the brain may be changing as well. A basic mindfulness exercise is to teach children to focus on breathing. Being able to control their breathing can help them become less reactive when stressed.

Focused breathing helps calm the body by slowing the heart rate, lowering blood pressure, and improving focus. Controlled breathing can override the fight, flight, or freeze response set off by the amygdala, and instead enable mindful behavior. My two-year-old son has learned to control his breath and to focus on his breath when he is frustrated—to my great astonishment. He is often able to calm himself when something doesn’t go his way and he gets agitated. He even reminds me to calm down when I’m anxious. He says “Daddy” and does a long inhale and a longer exhale. It’s pretty amazing. I started teaching him mindfulness with this simple breath exercise.

How to explain mindfulness and the brain to children

The amygdala – the jumpy superhero

The amygdala is like the brain’s super hero, protecting us from threats. It helps us to react quickly when there is danger. Sometimes it’s good to react—when there’s a real physical threat, like when you see a football coming your way. The amygdala simply decides that there’s not enough time to think about it and makes us react quickly: you move your head away from the path of the football. In this way, the amygdala can decide whether we get to think about the information our body gathers through our senses or not. But there’s a problem.

The amygdala can’t see a difference between real danger and something stressful. You could say it’s jumpy and that it makes mistakes. When we’re angry, sad, or stressed the amygdala thinks there’s real imminent danger. We then simply react without thinking. We might say or do something we regret immediately. We might even start a fight or just freeze when we’re offended, or supposed to take test, or speak in front of the class. Fear and stress shuts down our thinking in this way.

The prefrontal cortex – the smart one

The part of our brain that helps us make good choices is called the prefrontal cortex, or PFC. You could call it the smart one, as it helps you make smart choices and decides what is stored in your memory. To make good choices, the PFC needs to get the information our body gathers through the senses—sights, sounds, smells, and movements. The questions is: will the amygdala allow the PFC to analyse the information early enough? Remember: the amygdala, the jumpy superhero, often times hinders the information from going to the prefrontal cortex and we make rash choices.

This can happen when we’re angry, sad, negative, stressed, or anxious. What we want to do is to help the jumpy superhero calm down. But how? Here’s the trick. When we’re calm, the amygdala is calm and sensory information flows to the prefrontal cortex and we can make better choices. Even our memory improves when we’re calm and happy. We’re able to remember better and make new, lasting memories. So, how do we calm down so that the PFC, the smart one, has time to get and analyze all the information for us so that we make better choices?

Mindfulness practice to the rescue

Mindfulness helps us to calm down, and this, in turn, calms the amygdala so that it allows the information flow to the prefrontal cortex—that part of our brains that helps us make good choices. When we’re calm, we can more easily be mindful and make good choices. Scientists have figured out that the prefrontal cortex is more activated following mindfulness training and our high-level functions like the intention to pay attention, emotional regulation, body regulation, our communication skills, empathy, and our ability to calm and self-soothe are more available to us. Pretty cool, right? The more we practice mindfulness the more we’ll experience calm moments, even if we weren’t trying to be mindful.

How to do it?

When you feel overwhelmed, stop for a moment, take a few deep breaths and exhale slowly. Name the emotion you are experiencing. Focus on your breath for five breaths. See where you can feel your breath most easily—your stomach, your chest, or your nose. Control your breathing for a short while. Do deep belly breathing for five breaths.

Put your hands on your belly and feel how it expands as you breathe in. Multiple short mindful moments per day trains your brain to become more mindful even when you don’t try to be mindful. In other words, the more you train, the easier it will be to be mindful and self-soothe when you’re actually in a stressful situation.

I was fortunate enough to have started Tai Chi a moving meditation at a very early age. Practising Tai Chi for over 25 years has allowed me to build a solid foundation to support the most important aspect of EQ development, which is attention training.

If you are interested in supporting yourself or helping the teams you manage, the links below can help you learn more about EQ training.

- What is EQ?

- Emotional Intelligence Training Course

- Learn to meditate with the Just6 App

- Meditation and the Science

- 7 reasons that emotional intelligence is quickly becoming one of the top sought job skills

- The secret to a high salary Emotional intelligence

- How to bring mindfulness into your employee wellness program

- Google ’Search Inside Yourself’